As a 3-Year-Old, He Was Incarcerated.

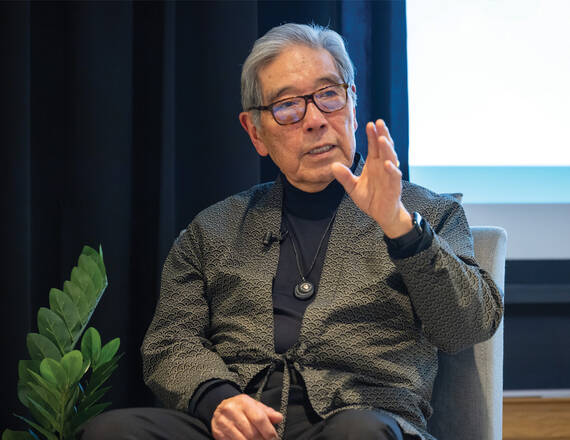

Now, Joe Okimoto MD, D ’60, MED ’61 Tells His Story.

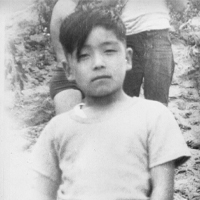

When Joe Okimoto MD, D ’60, MED ’61 was three years old, he and his family were arrested. Soldiers carrying rifles showed up at their door and ordered him, his pregnant mother, his father, and two older siblings into the back of a military truck.

Okimoto was one of nearly 125,000 Japanese Americans who were forcibly removed from their homes and imprisoned as targets of the U.S. government’s racist policies during World War II. He spent the next three and a half years in an American concentration camp in the Arizona desert—simply for having Japanese ancestry.

Now, 82 years later, after a psychiatry career focused on helping others who had experienced trauma, Okimoto is telling his own story publicly so that the atrocity of the internment camps is neither forgotten nor perpetuated. This year, on the anniversary of the date that President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which underpinned the incarceration of thousands of Japanese Americans, Okimoto spoke to the Dartmouth community in a Conversations That Matter event. For some of his classmates, it was the first time they heard details of his experience in the camp.

“Good people stayed silent” when the executive order was signed, Okimoto says, explaining that he sees it as his responsibility to share his story. “I shouldn’t remain silent.”

The Train to Trauma

Anti-Japanese American racism didn’t begin when Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. That policy was riding on the back of escalating racism in the wake of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. War Department propaganda encouraged others to view anyone of Japanese ancestry as a threat. People lost their jobs and were forced to drop out of school. The U.S. Department of the Treasury also froze some Japanese Americans’ bank accounts.

When Executive Order 9066 was signed on February 19, 1942, it granted the secretary of war and his commanders the power to relocate groups of people. Although Japanese Americans were not explicitly mentioned, the order quickly became the basis upon which anyone of Japanese descent was forcibly removed from their homes.

Okimoto’s family was sent to Poston War Relocation Center, the second-largest of the 10 concentration camps, which held around 18,000 Japanese Americans, regardless of whether or not they were U.S. citizens by birth—and the majority were.

Okimoto says his older sister remembers her fear of the soldiers outside their home. But at just three years old, Okimoto’s own memory from that time is spotty. And after a career researching and treating trauma as a psychiatrist, Okimoto suspects his “brain refused to retain it”—as memory loss is an established trauma response.

One of Okimoto’s few memories from this time is of being on a train, likely when the family was transported from a temporary prison camp to Poston.

“You know how the train jerks when it stops and starts?” he says, remembering “suddenly having the sensation that the world was falling away from under my feet. That must have been the panic of this upheaval.”

The Okimoto family spent three months in what was euphemistically called “an assembly center” before being transported to Poston. In reality, it was the Santa Anita racetrack, its animal stalls converted into temporary prison cells. “They didn’t get rid of the stench of excrement,” Okimoto says. While the family was there, Okimoto’s mother gave birth to his younger brother. Two weeks later, they were sent to the permanent concentration camp in the Arizona desert: Poston.

There, the temperature ranged from 115 degrees Fahrenheit to below freezing, with sandstorms a constant threat. The barracks, which were divided into 20-footsquare quarters by blankets and sheets, were not much protection. Hundreds of people shared toilet and shower facilities.

During Okimoto’s three and a half years there, in some ways, life was on hold. But in other ways, it marched on. Okimoto remembers having a tonsillectomy, and his brother recalls playing in the dust of the desert camp, fenced in by barbed wire.

Life After Imprisonment

When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in December 1944 that the War Relocation Authority could not detain citizens who had not been charged with “disloyalty or subversiveness” for “longer than...necessary to separate the loyal from the disloyal,” this lay the groundwork for Okimoto and the thousands of other Japanese Americans to be released.

But it wasn’t until September 1945 that the Okimoto family was finally released. They made their way to San Diego to attempt to restart their lives.

Okimoto’s experience of racism didn’t end in San Diego. “There was considerable anti-Japanese racism,” he recalls. “We kids went to public schools, and we were called racial slurs and chased home.”

Even when the intensity of the racism abated after the family left San Diego for a small town, the experience of being incarcerated lingered. Looking back at memories through a psychiatrist’s eyes, Okimoto recognizes that he and his family exhibited symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

From Concentration Camp to Medical Practice

Okimoto says he found the elite environment of Dartmouth extremely stressful as an undergraduate in 1956. He didn’t look like the predominantly white student body, he came from a relatively poor family, and he was far behind academically. And that, the now-psychiatrist says, tapped into the psychological damage from his childhood.

“It would be stressful for a lot of people, but for me, it was an emergency,” he says.

“Children who have been traumatized early, their brain can be altered as adults,” says Okimoto, who has reviewed psychiatric research on the impact of trauma on children. He explains that early childhood trauma affects the amygdala, the part of the brain that handles the fight-or-flight reaction. “In those who are traumatized, there is a hyperactivity of that amygdala. So there’s a tendency to interpret and react to things that are not truly crises as if they were.”

After graduating from Dartmouth in 1960, Dartmouth Medical School in 1961, and Harvard Medical School in 1963, Okimoto pursued a career in surgery. Meanwhile, as the civil rights movement of the 1960s grew, he decided to join the fight for equality, which prompted him to rethink his professional priorities. He left a surgery residency program to study health services delivery, and eventually ran a drug rehabilitation program, where he became deeply interested in psychiatry and human behavior.

“Looking back at that transition, I think I was trying to figure out where I could address my own healing and trauma,” the accomplished psychiatrist reflects decades later. “Trauma has been a much greater factor in the trajectory of my life than I realized. I don’t think I really saw it that way until I retired and began reflecting.”

In the early 1970s, Okimoto was appointed to Washington state’s first Commission for Asian American Affairs, and served as its first chair, advising the governor on how racism impacted the Asian American community. He also chaired the Asian Coalition for Equality, a community group that often joined in solidarity with African American civil rights organizations to protest institutional racism. In his psychiatry career, Okimoto maintained a private practice in Seattle until his retirement in 2016, conducting research in addition to that clinical practice.

When Okimoto began his psychiatry career, his support for the Asian American community became folded into his work, partially in the form of a part-time role as medical director of an Asian community mental health services clinic in Seattle. In his private psychiatry practice, he specialized in treating patients navigating challenges related to trauma.

Although Okimoto has “spent time on the couch,” in therapy, some of his own clients also helped him face the impact of his trauma. “Trauma is such a solitary experience—people don’t want to talk about it, and it’s difficult to only process it yourself,” he says. “To have another person listen and understand is an important part of the healing.”

For many years, Okimoto, his family, and others who were subjected to the American concentration camps didn’t talk about their shared traumatic experiences. “In most Japanese American families, it was never talked about. There was too much pain and shame,” Okimoto says. Until recently, “The only family member I talked with about the incarceration was my sister.”

His sister, in her own healing, began to dive into her memories of the years at Poston, share memories with others, and research and preserve the history of how the internment camps were built and what happened in them.

In 2018, Okimoto accompanied her back to the site of their incarceration, Poston. He expected long-buried memories to surface but they did not. “In a sense, I was disappointed,” he says. “I was hoping that something would come up that would help me with what I was struggling with in terms of healing.”

'Good People Can Contribute to Bad Policies’: Learning From The Past

Like his sister, Okimoto is working to preserve and retell the story of Japanese American incarceration during World War II to not only navigate his own story, but to remind society of the factors that fueled the policies that saw families locked up, and to prevent history from repeating itself.

Okimoto has joined a Japanese American organization called Tsuru for Solidarity. Tsuru, he explains, is the Japanese word for crane, symbolizing healing. The group brings together people who survived the incarceration and their descendants in both healing and in solidarity to speak out against injustices.

This is also why Okimoto is now telling the story of what happened to his family and thousands of others: “My current concern is that the contemporary political climate is such that certain segments of our society are voicing attitudes about immigrants and people of color very similar to those that contributed to my incarceration.”

Okimoto underscores the importance of recognizing how those who stayed silent when xenophobic or racist sentiments prevailed, or who perpetuated that hatred through art, propaganda, or everyday behaviors, contributed to a cultural era in which policies like Executive Order 9066 were signed.

“During that era, there were some voices in opposition to our incarceration but not enough of a critical mass that could alter the decision,” he says. “Too many voices were silent and turned away from the reality of racism.”

At that time, another Dartmouth alumnus was making a name for himself: author and illustrator Theodor Seuss Geisel D ’25, now commonly known by his pen name Dr. Seuss. Today, Geisel is most known for his books that frequently encourage equality and are used to teach kids about diversity, equality, inclusion, and kindness, such as, “The Sneetches and Other Stories,” and “Horton Hears a Who!”—which was published in 1954 and contains the famous line, “A person’s a person, no matter how small.” But earlier in Geisel’s career as a cartoonist, during World War II, Okimoto notes, he created propaganda to support the U.S. military. Geisel’s estate, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, pulled six of his books from publication in 2021, stating that they “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.” Geisel died in 1991.

Okimoto reached out to Dartmouth to share his own story in light of this lesser-known part of Geisel’s history. “Of course his gift [to the medical school] is very important, but the negative part of his legacy should not be omitted,” Okimoto told institutional staff. “Today, we are observing racism aimed at immigrant groups similar to what I faced during WWII,” Okimoto says. “This racism unfortunately demonstrates that even otherwise good people can contribute to bad policies and that as a country we must be vigilant in confronting racism in any form.”

Dialogues between Okimoto and the Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Community Engagement (DICE) at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth led to the Conversations that Matter event featuring Okimoto in February. The DICE office invited all alumni and Dartmouth at large to discuss ways in which our community can learn from injustices in the past to build a more inclusive, equitable, and just future.

“It was such a profound experience to hear Dr. Joseph Okimoto speak so we never forget the injustices inflicted upon innocent people who were incarcerated, treated like second-class citizens, and denied due process and equal protection guaranteed by the Constitution,” says Lisa McBride, PhD, Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging, who leads the DICE office at Geisel School of Medicine. “Dr. Okimoto’s courageous words made us remember the dangers of casting stereotypes of Japanese people. The stories he shared not only remind us of the wrongs in history, but also serve as a learning opportunity for all of us on how we should treat our neighbors and fellow citizens.”

McBride says that Okimoto’s message will stay with her and her team forever. “The DICE office aims to lead with compassion,” she says. “Our conversations with Dr. Okimoto reinforced our commitment to the work of dismantling the false belief in a hierarchy of human value, and to promoting truth, unity, and racial healing.”

Dartmouth looks quite different than it did in the 1950s, Okimoto said after speaking at the February event. “For me to look out in the audience and see the crowd and the diversity there, that was wonderful.” He adds that he feels a “deep appreciation for the educational opportunity that Dartmouth College and Dartmouth Medical School provided me before the advent of Affirmative Action programs in America. I realize that the Dartmouth education was a once-in-a-lifetime gift that changed the trajectory of my life.”