SweetGoals: Could Incentives and Coaching Help Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes?

When young adults begin leaving home for the first time, they become responsible for managing their lives without parent supervision. For those with type 1 diabetes, a chronic autoimmune disease that requires a complex medical regimen, this independence can put a strain on their health.

“Type 1 diabetes is often one of the most challenging chronic conditions to manage, and young people face unique obstacles when transitioning from pediatric to adult medical care,” says Catherine Stanger, PhD, professor of psychiatry and of biomedical data science at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and a faculty member at the Center for Technology and Behavioral Health (CTBH) at Dartmouth. “There are lots of things people with type 1 diabetes have to do every day for self-management, especially tracking carbs.”

And, Stanger says, their long-term health is at stake. About 70% to 80% of young people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) don’t meet the benchmark for healthy blood sugar levels. While they typically get better at glycemic control (blood sugar management) later in adulthood, Stanger explains that there’s a lifetime negative impact from any period of poor glycemic control—a “debt” that cannot be recouped.

This sobering fact was the impetus for Stanger’s work to help young people develop healthy habits early that they can maintain throughout their life. In a national randomized clinical trial, she’s currently testing whether two strategies—either financial incentives or human support through evidence-based health coaching—will help them do just that.

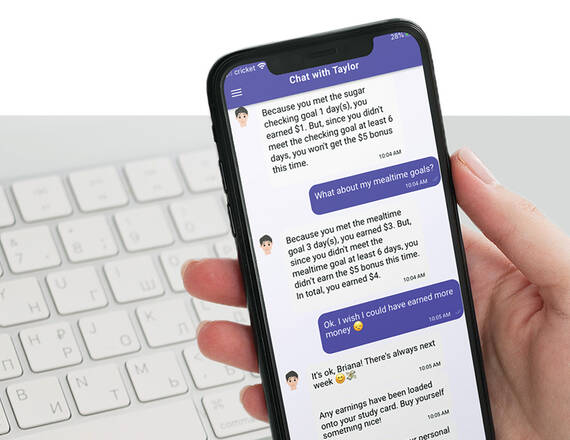

In the study, all participants, ranging from 19 to 29 years old, use an app that Stanger created called SweetGoals. This app integrates with participants’ diabetes device to set actionable weekly goals. During the six-month intervention, participants are also randomized to receive either additional financial incentives for meeting daily health behavioral goals, or to have live web sessions with a health coach. Some participants receive both financial incentives and coaching. Six months after the intervention ends, Stanger assesses whether the participants have maintained the healthy habits they developed during the intervention.

Stanger hypothesizes that, when supplementing the SweetGoals app, both coaching and financial incentives will independently contribute to improved day-to-day management and overall blood sugar control among high-risk young adults with T1D.

“This study uses existing evidence-based interventions, either a structured health coaching curriculum or a financial reward for engaging in clinically proven daily behaviors for healthy glycemic control,” Stanger says.

Stanger anticipates the results will reveal whether coaching or incentives—or both—are most effective. The first participants enrolled in 2021, and results of the study will be available next year.

“We don’t expect perfection in these behavior goals, but participants are building sustainable healthy habits,” she says. “When the incentive or coaching is removed, we hope they will maintain those habits.”

Translating Discoveries into Impact

Throughout her career, Stanger has been studying the efficacy of offering incentives along with counseling or coaching support for achieving health goals for people of all ages with many kinds of medical conditions. Some of her earlier work used incentive-based interventions paired with counseling to successfully address adolescent substance use, promoting abstinence and reducing substance use among teens. Her current T1D study is an adaptation of that research.

“The goal of this large clinical SweetGoals trial is to demonstrate powerful efficacy of these interventions and allow us to move to dissemination and implementation,” Stanger says. “There are a number of stages to this kind of work. SweetGoals is the result of a decade of work developed from smaller pilot studies and grants.”

Stanger’s work is housed in Dartmouth’s CTBH, which is funded through the National Institute on Drug Abuse. As the director of CTBH’s pilot core, Stanger facilitates the awards of one-year grants of up to $20,000 for researchers conducting innovative studies on digital interventions for health behaviors, many of which include a focus on substance misuse.

Early-stage discovery science, which puts researchers on the path to earning larger grants from bigger organizations, is often funded through philanthropy, says Lisa Marsch, PhD, CTBH director and the Andrew G. Wallace Professor of Psychiatry and Biomedical Data Science at Geisel. In the digital health landscape, expediting research is critical because technology changes so rapidly. Seed funding provides researchers the flexibility to test bold ideas and to take risks; to earn federal grants, researchers must already have proof of concept.

“As a center, we have the chance to fund pilot projects that hold lots of promise for digital health, especially mental health and addiction,” Marsch says. “We want to do more than rigorous science. With more resources, we can also do translational work—getting these technologies into the real world and into people’s lives. The pace of science and interpreting results and implementation is agonizingly slow. Philanthropy is meaningful in accelerating science and the scope of work we can do.”

To learn more about the Center for Technology and Behavioral Health, contact Bethany Solomon at 603-646-5134 or Bethany.Solomon@dartmouth.edu.