Healing the Symptoms of Emotional Dysfunction

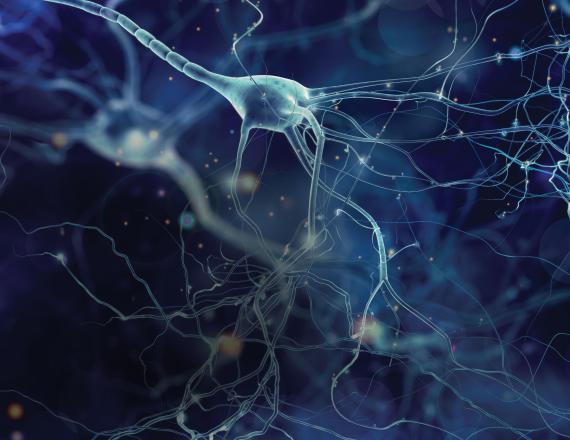

In patients with epilepsy who receive neuromodulation, electrodes in the brain monitor for seizure activity and send an imperceptible pulse to stop the seizure before it spreads—much like a cardiac pacemaker, which helps control abnormal heart rhythms. Krzysztof Bujarski, MD, a behavioral neurologist and epileptologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock (D-H) and associate professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine, is applying the same principle to problems of memory and emotional control that accompany a variety of neurological disorders.

“We can use technology to modulate sick brain regions,” explains Bujarski, whose research focuses on how people with brain disorders process emotions in daily life. “We can target small networks—the brain tissue involved is the size of a marble—and people don’t feel it, it doesn’t alter consciousness. What changes are the symptoms.”

Bujarski notes the example of patients who struggle with emotional or behavioral self-control or suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In these patients, the amygdala—a part of the brain responsible for emotional reactions— becomes overactive. Electrodes monitoring for such activity, Bujarski hypothesizes, could provide deep brain stimulation to quiet the function of the amygdala and relieve disruptive symptoms.

In a study at D-H of patients who already had electrodes in place, participants viewed visceral images, with some subjects receiving deep brain stimulation. Those subjects perceived the images as more neutral and were less likely to remember them—a finding with important implications for people with impulse control disorders or PTSD. Bujarski’s goal is to run additional clinical trials with patients who live with neurological conditions that induce emotional dysregulation.

“The objective of neuromodulation is to heal a specific brain network,” says Bujarski. “In time, the hope is that injured or diseased parts of the brain work normally again independent of stimulation.”